Corporate finance is used to describe activities, decisions and techniques that deal with many aspects of a company’s finances and capital.

Aswath Damodaran, professor of corporate finance and valuation at the Stern School of Business, New York University, explains how he tackles the subject.

Every decision made in a business has financial implications, and any decision that involves the use of money is a corporate financial decision. Defined broadly, everything that a business does fits under the rubric of corporate finance.

All businesses have to invest their resources wisely, find the right kind and mix of financing to fund these investments, and return cash to the owners if there are not enough good investments.

There are many versions of corporate finance that are taught.

There is the accounting version of corporate finance, that uses the historical, rule-bound construct of accounting as the basis for corporate finance. Decision making is driven by accounting ratios and financial statements, rather than first principles.

There is the banking version of corporate finance, where the class is structured around what bankers do for firms, with the bulk of the class being spent on areas where firms interact with financial markets (M&A, financing choices) and the focus is less on what's right for the firms, and more on how the deal making works.

My version of corporate finance is built around the first principles of running a business and it covers every aspect of business from production to marketing to even strategy.

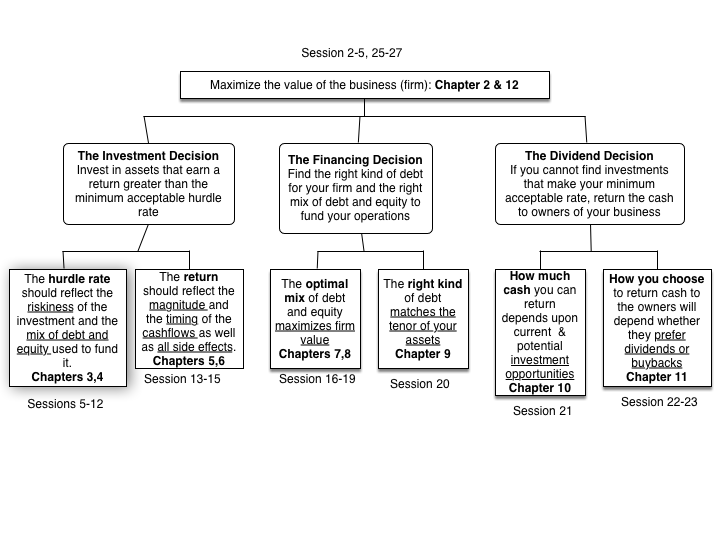

Every discipline has first principles that govern and guide everything that gets done within it. All of corporate finance is built on three principles: the investment principle, the financing principle, and the dividend principle.

1) The investment decision, where you should invest your resources.

Firms have scarce resources that must be allocated among competing needs. The first and foremost function of corporate financial theory is to provide a framework for firms to make this decision wisely.

We define investment decisions to include not only those that create revenues and profits (such as introducing a new product line or expanding into a new market) but also those that save money (such as building a new and more efficient distribution system).

Furthermore, we argue that decisions about how much and what inventory to maintain and whether and how much credit to grant to customers that are traditionally categorized as working capital decisions, are ultimately investment decisions as well.

At the other end of the spectrum, broad strategic decisions regarding which markets to enter and the acquisitions of other companies can also be considered investment decisions.

2) The financing decision, where you decide the right mix and type of debt to use in funding your business.

Every business, no matter how large and complex, is ultimately funded with a mix of borrowed money (debt) and owner's funds (equity).

With a publicly trade firm, debt may take the form of bonds and equity is usually common stock. In a private business, debt is more likely to be bank loans and an owner's savings represent equity.

Though we consider the existing mix of debt and equity and its implications for the minimum acceptable hurdle rate as part of the investment principle, we throw open the question of whether the existing mix is the right one in the financing principle section. There might be regulatory and other real-world constraints on the financing mix that a business can use, but there is ample room for flexibility within these constraints.

3) The dividend decision, where you determine how much to hold back in the business (as cash or for reinvestment) and how much to return to the owners of the business.

Most businesses would undoubtedly like to have unlimited investment opportunities that yield returns exceeding their hurdle rates, but all businesses grow and mature. As a consequence, every business that thrives reaches a stage in its life when the cash flows generated by existing investments is greater than the funds needed to take on good investments. At that point, this business has to figure out ways to return the excess cash to owners.

In private businesses, this may just involve the owner withdrawing a portion of his or her funds from the business. In a publicly traded corporation, this will involve either paying dividends or buying back stock.

When making investment, financing and dividend decisions, corporate finance is single-minded about the ultimate objective, which is assumed to be maximizing the value of the business.

These first principles provide the basis from which we extract the numerous models and theories that comprise modern corporate finance, but they are also commonsense principles.

It is incredible conceit on our part to assume that until corporate finance was developed as a coherent discipline starting just a few decades ago, people who ran businesses made decisions randomly with no principles to govern their thinking. Good business people through the ages have always recognized the importance of these first principles and adhered to them, albeit in intuitive ways. In fact, one of the ironies of recent times is that many managers at large and presumably sophisticated firms with access to the latest corporate finance technology have lost sight of these basic principles.

Here is what it looks like:

The above extract has been taken from Aswath Damodaran's blog and his shared views.