This article is an extract from a very detailed post written by Laurence Seigel and Stephen Sexauer that appeared in the CFA Enterprise blog.

Our parents, grandparents, and ancestors lived with the risk of polio, smallpox, plague, cholera, typhus, and a host of viruses and bacterial infections in the epic battles between human beings and infectious disease. They didn’t live happily with these risks, but humanity survived.

What is new this time is that public authorities in much of the world have issued emergency orders that have locked down large swaths of economic and social activity.

Schools, restaurants, religious services, weddings, and funerals, as well as many of the factories and offices that produce the world’s goods, have all been shuttered. Internal and external travel restrictions have compounded the economic paralysis.

These lockdowns, which can be beneficial when properly deployed, have delivered an enormous economic shock — one so large, it is a “crisis” by any historical measure.

But we do not expect Great Depression 2.0.

Why? Because unlike the first Great Depression, this one was imposed by political authorities in an attempt to control the spread of a virus. What can be imposed from above can be relieved from above.

When the virus is controlled and the restrictions are lifted, pent-up supply and pent-up demand will collide. The boom could be tremendous as workers rush to reclaim jobs and begin to spend confidently, and as capital, of which there is no shortage, is deployed in recapitalizing damaged businesses, many of which will be under new ownership.

The trick is achieving a balance between two goals: the need to control the virus so the coming boom is not stopped in its tracks, and the need to avoid any more capital destruction than is absolutely necessary.

The effects of an economic shutdown are nonlinear.

A 2-week shutdown is like a long, boring vacation.

A 2-month shutdown is a monumental pain in the neck, but one we can recover from.

Beyond two months and basic infrastructural goods and services begin to fall apart. Human capital decays as people’s skills atrophy, and our children’s intellectual growth stagnates as they miss more and more school.

We are approaching five months with only a moderate liberalization of economic activity. After two years, we’ll likely be headed back to the Dark Ages. We don’t know if the trip will send us to 1993, 1933, or 1333. But, whatever the destination, we cannot let that train leave the station.

We do expect some changes in behaviour to occur, but they won’t alter our basic nature: Humans seek out connection and try to make progress. People adapt well to new normals that bring that connectedness and progress: It’s no mystery why today’s internet, mobile phone, and social media firms have been the fastest-growing global companies the world has ever seen. Apple is the largest company by market cap in the world, almost equal in value to the whole Russell 2000 (!).

Amazon is everywhere. Facebook has 2.6 billion users — one out of every three men, women, and children on the planet. Zoom went from an unknown company to a global giant in less than a year.

People will strive to return to their old normal lives, and they will pull along the parts of the new normals that they like. Social interaction — for business, education, family life, fun, and spiritual renewal — is just too valuable to abandon in pursuit of an illusory bubble of safety.

Just as the social distancing of the 1918–1919 flu pandemic soon gave way to the Roaring ’20s and widespread electrification and work-saving appliances, among other innovations, and the little-remembered but very serious 1957–1958 flu pandemic yielded to the groovy 1960s, the medium-term future will look a lot more like “business as usual,” enhanced by innovations, than it will the dreary present.

The Utilitarian Calculus

The only way to balance the conflicting COVID-19 needs, dangers, and short- and long-term goals is to think of them as an optimization problem that requires balancing decisions to achieve the highest utility when summed across all people.

This balancing act goes back to Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian calculus, an Enlightenment-era attempt to put numbers to happiness and tragedy that has annoyed those who do not understand it ever since.

The utilitarian calculus holds that any action should maximize the summed utility of all the people in the world, taking into account positive and negative aspects of utility — death is very negative but it is possible to imagine a fate worse than death — and including the effects that you can see and those you cannot.

Utilitarian-calculus problems are familiar to philosophy and ethics students: How many trolley passengers would you sacrifice to save a pedestrian?

This way of viewing ethical problems is not the right way to frame the COVID-19 dilemma. It is the only way. Many object to utilitarianism on the grounds that there are moral absolutes. But extreme examples and polar cases are revealing.

For example:

Would you be willing to reduce the world’s economic output to exactly zero — meaning nobody eats, starting right now — to save one life? Of course not. So there is a number, an unacceptable level of cost, beyond which the saving of one life requires too much sacrifice from everyone else. At the other pole, would you pay one dollar to save that life? Of course, you would. So between those two extremes of cost, there is an equilibrium.

That equilibrium, wherever it lies, is the utilitarian solution to the problem. Of course, we don’t know what that solution is, but we know there is one.

One can begin by framing the problem in the right terms.

This “utilitarian calculus” may seem cold, but it is at the heart of humanism, the philosophy to which we subscribe and upon which Western civilization is based. It is part of the political economy of how we organize to provide commonwealth goods and maintain our personal and economic freedoms. Without it, how else can we make pandemic-related decisions that involve trading years of life now against years of life in the future? Any other framing necessarily leads to a narrow, suboptimal solution that will favor one person or group over another for no morally acceptable reason, or worse, yields to full external control of everyday life.

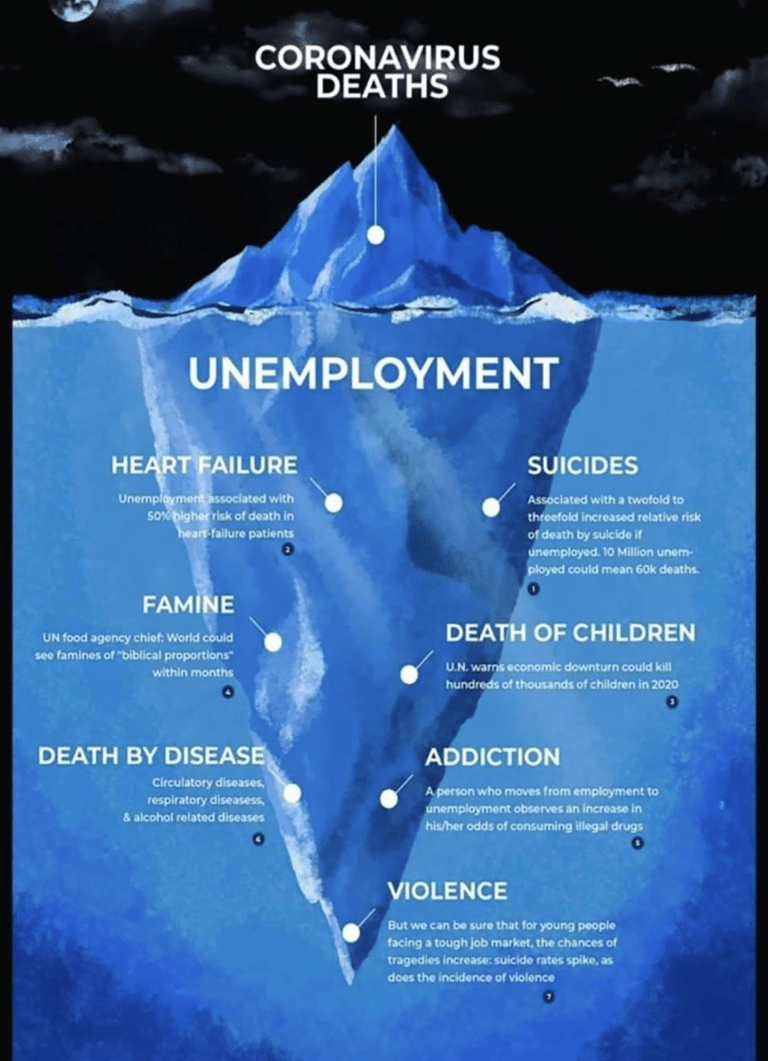

The COVID-19 Iceberg: What Can and What Cannot Be Seen