I met SLOANE ORTEL a few years ago in Mumbai. And my instant impression was of an amicable, genuine and easy-going human being. Sloane’s struggle with gender dysphoria, and transition from being a firm believer in passives to an active investor is fascinating.

She shares it here, in her very own words.

Our relationship with money is shaped by our childhood influences. It is often our parents who teach us our first money lessons.

My parents were both enterprising in their careers and open with their experiences as I was growing up. Their shared interest in the capital markets made for interesting conversation on long car rides.

My mom liked to joke that she taught me the difference between debt and equity before I could ride a bike. Mom eventually left her career at Lehman Brothers to teach AP economics at Stuyvesant High School.

My dad is one of the most insightful analysts I’ve ever met. In 2007, he was warned about leverage in the financial system and pushed the investment community to re-evaluate companies like General Electric that had become addicted to financial engineering. (I occasionally watch his TV appearance as a reminder of how deeply the market can misunderstand a company.)

Despite such fantastic childhood influences, I struggled to understand why individual investors should invest their money in anything but index funds.

An investor who decided to bet against GE after dad’s interview aired would have had to incur significant cost, manage mechanical complexities, and wait close to a decade for the insight to deliver any benefit to them.

And in the meantime, a simple index fund investor would have compounded their capital faster and had more time to think about other things.

That’s what I call a win-win.

When I was 19 years old, I worked as an intern at what’s now the Grand Central Private Client Group (then known as Oppenheimer & Company). I was paid $15 an hour to build spreadsheets that described clients’ financial situations and our associated asset management positioning.

I got to meet with fund managers, build models, and generally research stuff to my heart’s content. I also had unrestricted access to a Bloomberg terminal, which was one of the more exciting developments of my adolescence.

Joining CFA Institute in 2010 gave me an opportunity to dive deep into state-of-the art academic research that surrounds the practice of investment management. My sole responsibility was to highlight tools, tactics, and technologies that investment professionals make better decisions on behalf of their clients. I began to develop the organization’s online community-building efforts and recruited expert voices to share their thoughts, in what eventually became the Enterprising Investor.

I added my own voice into the mix, and even wrote a book with my friend and mentor Jason Voss.

I still couldn’t see why individual investors would want to invest in anything but an index fund. My confidence in indexing – a simple and straightforward approach, only grew as I gained more information.

And then I came out.

I experienced gender dysphoria my entire life. In 2017, I finally felt able to do something about it besides distracting myself. I changed my name, my appearance, and my pronouns with the benefit of a supportive work environment, then prepared myself for whatever might happen when the rest of the world noticed.

The years I’ve spent connecting to other queers since coming out have taught me to take my values seriously, hold myself accountable to my best intentions, and continuously improve my ability to listen.

They have also made me comfortable with who I am. I started a podcast to explore how the world’s most sophisticated investors were working to build a better future for finance, and began writing the Inclusion in Wealth column for Citywire RIA to explore issues around diversity, equity, and belonging in our industry.

The turning moment was when my girlfriend and I sat down to have the conversation about how we would invest our money. Before I offered a full-throated defense of index funds and passive management, we enumerated our values.

It turned out that I held some pretty extreme views.

Specifically:

- Companies should pay their taxes,

- Avoid preventable harm to living things, and

- Care for the communities where they operate.

Though I’ve expressed them fairly concisely above, those values actually summarize a two page, single spaced policy that excludes companies with questionable products, conduct, or both from our investment strategies.

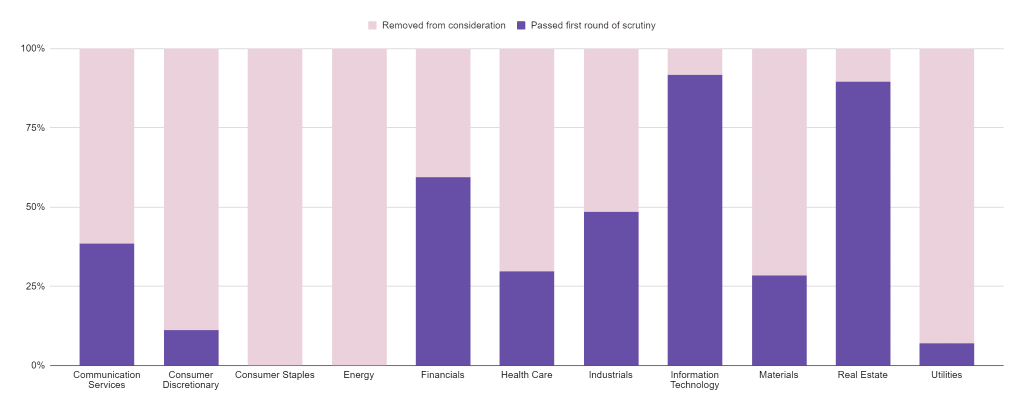

But however well-constructed our policy is, it’s unlikely to produce compelling results unless it’s part of a coherent investment process. It’s pretty easy to see why: here is a chart of what happens when you apply our criteria to the S&P 500 index.

Each column represents an economic sector. The purple part indicates the percentage of companies in that sector that can make it through our screens. When it’s just pink, it means none of the companies made it through.

You’ll notice it varies widely, and that the folks in tech and real estate seem to perform much better than the rest of them.

There’s a simple reason for that: our screening process isn’t good enough.

It can’t be.

The capital markets are literally a manifestation of the world’s current power structure. Anything that people do will find a way to concretize in the capital markets somewhere. So eventually I realized there is no checklist comprehensive enough to rely upon.

You have to pay attention.

Because companies often talk a big game, but are absent when it comes time to come through for their communities. Because our goal is not just to identify companies that are shaping the world positively but also generate financial stability for our clients. So can’t just buy the stuff that makes it through the screens and pretend I’m making the world a better place.

Are index funds bad?

Far from it! I have Jack Bogle’s autograph sitting above my desk, and I still think that they do an excellent job growing people’s money without requiring much in the way of oversight or critical thought.

They just have nothing to do with ethics.

And as an ethics-first investor, I owe it to everyone evaluating my strategy to be clear that there is substantial independent judgement and discretion involved in what we do.

We do not “set and forget” anything. My purpose in starting Invest Vegan is to support a restless search for better, more complete, and more reliable investment options than currently exist. And there is nothing passive about that process.

More Money Stories

This advice will revolutionize your relationship with money: Dr. Farah Usmani

A money mistake that cost me dearly:

Ritushree Panigrahi

3 money lessons you cannot ignore:

Shreya Singh Dalal

5 Money DON'Ts that every women must know

:

Padma Ramarathnam

Advice to my 20-year-old self:

Zainab Jabri